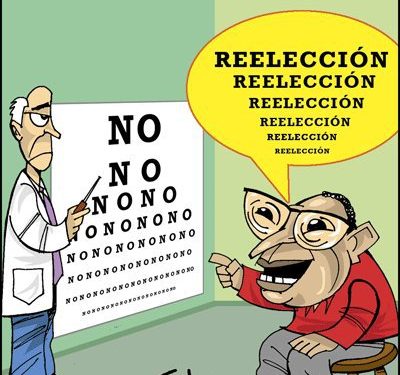

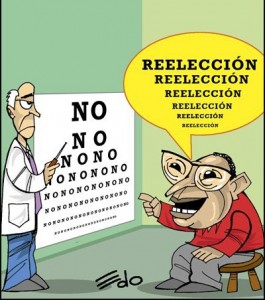

This was the aspiration of the late President Hugo Chavez. He introduced it in the Constitution of 1999. He intended to expand it in 2007, but met the refusal of the majority of the people. Then in 2009, thanks to the popular vote expressed in a referendum, he finally attained his cherished goal: the indefinite re-election. In this effort to break the limits to his stay in Miraflores, Chavez was not alone. On the contrary, he had the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court as one of his main allies. On July 28, 2006, before the Head of State proposed to reform the Constitution to remain in power, the country’s highest court upheld the proposal of the ruling party.

This was the aspiration of the late President Hugo Chavez. He introduced it in the Constitution of 1999. He intended to expand it in 2007, but met the refusal of the majority of the people. Then in 2009, thanks to the popular vote expressed in a referendum, he finally attained his cherished goal: the indefinite re-election. In this effort to break the limits to his stay in Miraflores, Chavez was not alone. On the contrary, he had the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court as one of his main allies. On July 28, 2006, before the Head of State proposed to reform the Constitution to remain in power, the country’s highest court upheld the proposal of the ruling party.

“Re-election in our system does not imply a change of regime or in the form of the State, on the contrary, it reaffirms and strengthens the mechanisms of participation in a democratic state, with social justice and under the rule of law established in the 1999 Constitution. Likewise, re-election expands and provides continuity to the right of choice of citizens, and optimises society’s control mechanisms over their rulers, making them examiners and direct judges of the administration that seeks re-election, and therefore constitutes a true act of sovereignty and exercise of direct social control,” ruled the Court in a presentation by TSJ Presiding Justice Luisa Estella Morales. And not only that. Morales went as far as to rule that the Venezuelan president was not obliged to leave office to seek re-election. In other words, he could lead his election campaign without giving up his powers and privileges.

The Supreme Court did not always think that way. In fact, the judgment of the Constitutional Court – which ended up prevailing – discredited the resolutions of the Electoral Chamber on March 30, 2006, which in judgment of the electoral commission of the Savings Bank of Public Sector Employees stated: “a ban on successive re-election is a legislative control technique resulting in inconvenience that a citizen remains in power indefinitely, claiming, among other things, to reduce his ability to influence of the incumbent, and especially to preserve the need for candidates to be on the same footing, and so elected officials do not distract their efforts and attention on matters other than the complete realisation of their administration.”

The Electoral Chamber substantiated the ruling by recalling that on March 18, 2002, it had ruled that “the above ‘right’ of re-election, although justified as a means of continuity of good governance, could lose its merit and become a serious threat to democracy: the desire for perpetuation in power (continuity) and the obvious advantage of incumbents in electoral process, have caused in Venezuela and elsewhere in Latin America a deep rejection of the concept of re-election.”

Contrary to the opinion of their peers, the members of the Constitutional Chamber shielded the legality of indefinite re-election, opening the door for “perpetuation of power” in Venezuela.

Extract of the judgment

“Re-election in our system does not imply a change of regime or in the form of the State; on the contrary, it reaffirms and strengthens the mechanisms of participation in a democratic state, with social justice and under the rule of law (…). Likewise, re-election expands and provides continuity to the right of choice of citizens, and optimises society’s control mechanisms over their rulers, making them examiners and direct judges of the administration that seeks re-election, and therefore constitutes a true act of sovereignty and exercise of direct social control”.